The mother of the modern Superbike

Superbikes

‘Was the GPz900R a superbike?

I always hear derisive snorts when I suggest this to modern riders (grin), but remember we aren’t comparing the bike to today’s machinery, we are comparing the bike to what was on the road in 1984 (or before).

The complete performance package of the GPz900R was not simply the fastest but more importantly it was ridable & affordable to the common rider, cutting a new pathway for the development of the performance motorcycle.

E=mc²

Enstein’s Theory of General RELATIVITY.

The GPz900R was the first motorcycle that meant a normal (ie not racer) rider had production machinery that could match or surpass almost anything else on the road – even supercars.

When the iconic CB750 was released in 1969 there were around NINE +150mph supercars. Yes they were rare, and if you measure a production car as building more than just 100 then this list drops to maybe just FOUR. But they were significantly faster than bikes.

And although modern superbikes are extraordinary motorcycles, supercar development has been even better – so the performance gap between superbike & supercar has widened again from the GPz900R.

Simple physics (especially high-speed aerodynamics & tyre temperatures) suggest that the gap between superbikes & supercars will remain (or extend) for the foreseeable future, a reality which further highlights the relative performance of the GPz900R when it was released in 1984.

2020

The Ninja ZX-14 is one the fastest production (ie not race spec) superbikes at 208mph and a genuine sub-10s 1/4 mile machine, yet here’s a list of 100 production cars that all top 217mph and TEN supercars that all theoretically run sub-10s quarters.

As a measure of modern performance improvements there are now over 40 cars that can match the GPz900R over the 1/4 mile! In 1984 there were NONE.

1984

In 1984 the +150mph GPz900r was the fastest production bike ever made and only beaten in top speed by around a dozen cars. This also shows the exclusivity of the supercar at that time, as only TWO of these, the Studebaker Avanti and the Porsche 930 had total production runs over 1,000 vehicles. They were also challenging to produce economically, with only perhaps FOUR new cars produced from 1969 to 1984.

The 1984 296hp Porsche 930 was listed as 162mph, 0-60mph in 5 sec and 1/4 mile in 13.7. So by the 1/4 mile the GPz900R was over 2.7 sec ahead, an eternity in drag racing. And with the frightening handling characteristic to over-steer mid-corner when the boost came on, I’d suggest any Porsche that matched the GPz cornering was probably needed to be piloted by a racing driver.

Interestingly this was definitely a car whose power overwhelmed it’s chassis, just like the performance bikes that precede the GPZ900R. The difference is on a bike poor handling traits at speed are guaranteed to end in major injury or death. The Porsche was easily the most affordable supercar of it’s time, but were they driven hard on the road? Unlikely.

Without really trying my old detuned A8 (108hp) can easily reach an indicated 220km/h in less than 1km (The Bend racetrack straight, 2020) so whilst a 1984 supercar might eventually catch an A1 (115hp) – it was going to take some serious road in a car that cost an absolute motza (except maybe the Studebaker!).

Important*

Back in 1984 the world wasn’t quite as clinical (or maybe cynical-lol!) so performance figures, especially those provided by the manufacturers, all needed to be taken with a grain of salt. A real-world tested BB512 speedo read a maximum of 174mph at a true 163mph and recorded a 6.2sec 0-60mph vs the claimed 5.1. And when they compared gearing with max RPM the factory quoted max speed simply didn’t add up…..marketing!

The sub 3s and sub 11s acceleration figures for the GPz900R were from journalist reviews (not Peewee Gleason) however that doesn’t necessarily mean it was a stock bike, same track conditions, etc.

However simple power-to-weight ratios show the GPz900R would have had a significant acceleration advantage over any of it’s contemporary supercars – even the 930 would need over 800hp to be close.

So the GPz900R it is universally acknowledged as the first +150mph production bike, it handled better than any past or contemporary top-end performance motorcycle, it was one of the fastest accelerating motorcycles ever made & at that time meant it accelerated significantly faster than any other car on the road.

There was only a dozen supercars with a faster top speed, most of these rare and expensive, and off the line they had to catch it first.

Pretty super huh?

The definition of Super (prefix)

The answer is: 42

This is a literary reference to Douglas Adam’s 1979 novel ‘The Hitchhiker’s guide to the Galaxy’. An intergral point of this great sci-fi comedy is that that the answer to complex questions is meaningless unless you can actually define the question in an understandable way.

So what is a superbike?

What we soon realise is that superbike has meant different things, to different people, at different times, and what is interesting is that even today there is still no clear definition.

If manufacturers have not wanted to create a specific definition then this suggests that the superbike is a marketing definition.

However these would be some widely accepted (public & industry) criteria for a superbike:

- high speed & handling (high performance)

- competiton oriented

- technologically advanced

All of these tend to make the superbike expensive, thus it is economically exclusive. This exclusivity means the superbike will generally have a lower volume of sales, so it is rarer on the street than other models. If this exclusivity can then be channelled into ownership desirablility then economics are no longer critical – so the superbike no longer needs to be a value-for-money motorcycle.

Superbike & Supercar template

- high performance = economic exclusivity + uniqueness

- exclusivity + uniqueness = desirability (by owner & observer)

- desirability as important as value-for-money

- high performance potential but still accessible to low skilled owners

It is important to clarify that for many owners performance, technical specifications and suitability for competition are important purchasing criteria. But these are not the core criteria for a manufacturer.

The marketing beauty of a modern supercar is that new or low-skilled owners can drive them – and never use them anywhere near their perfomance limits. The marketing brilliance of the modern superbike is that new or low-skilled riders believe they can own and ride one safely.

Whether that is good or bad is a completely different discussion!

1948. The Vincent Black Shadow HRD

This bike could do 125mph (200km/h), and if you do not know some of the details of this motorcycle – you should!. This was an amazing piece of machinery (eg. engine is a stressed member) and I totally concur with this bike being the godfather of ALL superbikes.

As is the case when evaluating the influence of the GPz900r (1984) – performance is relative to then (1948), not now. In 1948 this was the fastest motorcycle on earth and only beaten in top speed by a handful of cars. However all fast motorcycles of that era (and the decades that followed) required exceptional skill (or bravery) to ride fast. It was complex to produce and the company simply could not build these wonderful motorcycles at a profit.

- high performance = economic exclusivity + uniqueness

- exclusivity + uniqueness = desirability (by owner & observer)

- desirability as important as value-for-money

- high performance potential but still accessible to low skilled owners

The Vincent highlights a key difference in attitudes back then, an extraordinary world where straight line world-speed records were often used to measure of a production motorcycles perfromance! Making fast motorcycles safer for the average (or reckless) rider simply wasn’t a high design priority.

Super bike? – absolutely. Superbike? – absolutely. Modern Superbike? – no.

1969. The Honda CB750

History generally shows that when manufacturers put significant R&D into creating a new motorcycle the results are usually pretty darn good.

Pick a superlative and use it – the Honda CB750 was genuinely that good & one of the greatest motorcycles – ever.

It is considered to to be the first motorcycle that the press called a ‘superbike’, and understandably.

However a significant British nod must be given to the Triumph Trident/BSA Rocket 3 , a similar motorcycle actually released four weeks before the Honda in 1969. As with the GPz900r it shows that new motorcycle designs are often being developed in parallel and in complete isolation by different manufacturers. The running prototype for this motorcycle was ready as early as 1965….

Curiously not especially liked by the US public, despite (IMHO) the designs being very simiar. Maintaining the Triumph legacy (from bikes like the Bonneville) the Trident was no slouch, setting 4 world speed records at Bonneville. But with drum brakes (vs disc), 4-speed gearbox (vs 5), push-rod valves (vs overhead), and a kick-starter (vs electric) the Honda was technologically far more advanced and rider friendly.

Like most British bikes of that era the Triumph was expensive to build, service & maintain and it was completely overshadowed by the Honda as the next-big-thing in motorcycling – with annual US sales probably fifteen times the volume of the Triumph.

Every japanese performance motorcycle can trace some of it’s DNA back to the CB750 and it’s influence clearly extended to every motorcycle manufacturer on the planet. It was technologically advanced & powerful yet reliable & rideable – it simply stood head & shoulders above the rest. But the CB750 design wasn’t really about performance, it was never designed to be the ultimate performance motorcycle. So despite the significance of the motorcycle I don’t consider it a modern superbike.

- high performance = economic exclusivity + uniqueness

- exclusivity + uniqueness = desirability (by owner & observer)

- desirability as important as value-for-money

- high performance potential but still accessible to low skilled owners

This is not a criticism, back then the primary goal of the Honda was to expand into the US market, so economics would have been a more important design criteria than performance. The fact that the motorcycle was so good yet built to a competitive price point is just further evidence as to how amazing the design was.

This motorcycle made large-capacity powerful motorcycles accessible to the wider community.

Super bike? – absolutely. Superbike?- absolutely. Modern Superbike? – no, but incredibly important.

What makes the CB750 and the GPz900r super-special is that both Honda & Kawaski weren’t reacting to the market nor catching up to competitors – they dedicated significant R&D, time & resources (and risk) with a focused goal of creating a significantly better motorcycle – at a competitive price.

1976-1988. Superbike competition (AMA & FIA)

In competition terms, superbike racing was a concept originating in the US (1973) to allow enthusiasts to race modified production bikes at a ‘reasonable’ cost – the ‘super’ versions of showroom models. The first race was won by a Kawasaki Z1 (heavyweight) and the Yamaha RD350 (lightweight) – iconic motorcycles and the perfect examples of the generation of performance bikes that preceded the GPz900r.

So from a competition perspective both of these bikes, as well as ANY other bike that raced – was a ‘superbike’!

In 1976 it became an official US (AMA) category and in 1988 became an international (FIM) sanctioned class, with the modern defined as.

The motorcycles that race in the championship are tuned versions of motorcycles available for sale to the public, by contrast with MotoGP where purpose built machines are used. MotoGP is the motorcycle world’s equivalent of Formula One, whereas Superbike racing is similar to touring car racing.

Homologation - what it means

MotoGP bikes are custom designed for just the racetrack – they do not need to have any resemblance to any other bike – competition or road. The Law of Diminishing Returns makes success at this level of any motorsport incredibly expensive.

Competition superbikes are a production class – they are intended to be a variant of the same bike that you can buy at the showroom, so (in theory) reduce the cost to both manufacturers & owners and are great marketing. Homologation is a fair-play rule that requires (along with other requirements) a certain number of these bikes to be made available to the general public before they can be used for official racing.

In Australia one of the great stories of “homologation” is “Godzilla” – The car the ate Bathurst. Nissan struggled to sell the required 100 R32’s at $110,000 – huge money in 1992 (double it for 2020) for a Japanese car and even scarier given today’s insane house prices…… If anything what it shows is that when it comes to competition the “rules” are often way behind realty, the desire to win and even the general public’s interest in the sport. Arseholes right?….LOL.

Obviously the more competition-oriented the original motorcycle design the better suited it will be for racing.

The conundrum is that positive design traits for racing are nearly always negatives for road use – something noted way back in 1984 with the release of the GPz900R.

1983. The Honda VF750f Interceptor

Aha, now we can see the modern sportsbike. The lovely Honda VF750f was the purely sports version of the 1982 V45 Sabre, specifically targeting the 1983 superbike championship where capacity was limited to 750cc.

Instead of racers taking the production bike & modifying UP for competition, Honda optimised the bike for the superbike competition and then adjusted DOWN for street use (and homologation) which meant the bike could easily revert back to competition mode.

This was a significant manufacturer decision (& investment) that resulted in awesome motorcycle that dominated the superbike category.

- high performance = economic exclusivity + uniqueness

- exclusivity + uniqueness = desirability (by owner & observer)

- desirability as important as value-for-money

- high performance potential but still accessible to low skilled owners

Super bike? – yes. Modern Sportsbike – absolutely. Modern Superbike? – close but no.

Square-tube perimeter frame, single seat configuration, wonderful engine & handling, a competition success and a sweet looking motorcycle. But a modern superbike it needs to be (or perceived to be) the ultimate performance motorcycle, and the 750 Honda simply didn’t have the performance to run with bigger-engined competitors.

Although it probably didn’t influence the GPz900r (already well in development) the Honda showed that capacity wasn’t everything, and it is the sum of all parts working together that make exceptional motorcycles.

Many look back at the Ninja as the ‘big Kwaka’. But this was a time when most manufacturers increased performance by increasing engine capacity – Kawasaki themselves had the z1300 – yet the little GPz900r beat them all.

The modern Supercar

Hang on, what does this have to do with motorcycles?

Well the supercar industry was created long before the superbike industry – and as described the design template is the same.

We sometimes forget that there have always been very fast cars….in 1963 the Studebaker Avanti could top 168mph.

Generally recognised as the first supercar, 1966 Lamborghini Miura (0-60mph in 6.3 sec & 163mph) and the 1967 Ferrari Daytona (0-60mph in 5.4 sec & 174mph) were fast. Contemporary performance bikes like the Triumph Bonneville or the Norton 650 had similar acceleration but only a 110-115mph top speed. Recognised as fine bikes of their generation they still required significant skill (and nerve) to ride hard – and good luck stopping quickly with the drum brakes of that era!

So for a very long time performance cars were simply much, much better than performance motorcycles. Even the incredibly modern 1969 Honda CB750 was (0-60mph 10.0sec & 97mph) was no match for these cars. Fast forward to 1984 and the four genuine contempary production supercars were:

- Lotus Esprit Turbo: 0-60mph in 6.1 & 150mph top speed.

- Lamborghini LP500S: 0-60mph in 5.2 & 182mph top speed

- Ferrari BB512: 0-60mph in 5.2 & 179mph top speed

- Porsche 911 Turbo: 0-60mph in 5.1 & 162mph top speed

Note: these numbers show how impressive the performance of the Daytona & the Miura were – even today.

And whilst in 1984 there were other motorcycles that could out-accelerate these supercars (eg. z1300 4.0sec) engines simply over-powered & over-whelmed the chassis of performance motorcycles of this generation, they were not easy to ride near their speed limits. There were no full fairings to provide decent rider protection (the Katana wasn’t bad though) and at these speeds aerodynamics was simply becoming critical rather than optional.

The GPz900r (0-60mph in 2.9 sec & 151mph) was the first modern motorcycle that could genuinely match contempary supercars on the road.

They may have a higher top speed, but dues to the significant acceleration advantage and high-speed cornering ability it would take a serious amount of road to catch a Ninja off the line.

It’s still one of the fastest accelerating production bikes – ever.

This seems impossible given the serious increases in power and tyre sizes of modern machinery, but it’s probably related to the pure physics of getting the power down. The GPz900r has a longer wheelbase and greater rake than modern bikes, design features that help keep the front wheel on the ground. Just look at drag bike design. It also runs an 18″ rear wheel – which means a longer contact patch and lower rotational speeds (for the same linear distance) than a modern 17″ rim. Modern bike’s easily overwhelm the rear tyre so they need electronics to prevent both wheelies and wheel-spin but this effectively reduces the power delivery at the rear wheel. The GPz900r seems to have a natural balance between power & traction that surprisingly means it acceleration is still right up there with many modern larger capacity motorcycles.

But perhaps the most relevant aspect of these 1984 supercars was that despite both Lotus & Ferrari running Formula One cars, ONLY the Porsche was ever used as a serious competition car. So whilst a modern supercar may benefit from a manufacturer racing pedigree, it was no longer critical. In fact most supercars today have no direct connection with motorsport vehicles, and IMHO 99% of these vehicles will never touch a racetrack in anger.

Even when you read reviews of supercars discussion is about looks, style, cost, exclusivity as much as performance!

And the key factor is drivability; to make it available to the widest target audience the modern supercar needs technology allowing the chassis & engine power to be manageable by an average skill driver. The same applies to superbikes, the only real difference is economics. Supercars are definitely in the if you need to ask you can’t afford it category!

Following 1984 the key milestones of the modern supercar were the 1987 Porsche 959 and the 1988 Ferrari F40, the last of the great Enzo’s cars. Enzo was a legend; “My cars are designed to go, not to stop.” sums him up perfectly! The Ferrari had amazing performance, exclusive brand, immensely desirable. But it was a track car, difficult to drive & terrible on a public road.

The Porsche could not have been more different. Still extraordinarily fast (198mph – how that last 2mph must have irritated the Porsche engineers!) it’s legacy was that it was bristling with techno-wizardry that meant it could be driven fast by anyone (unlike a 911 Turbo) in relative comfort. But as a driving experience it was considered dull in comparison to the Ferrari.

The next car Ferrari released was the F50 – blending the desirability the Ferrari F40 with the drivability of the Porsche 959.

The modern supercar was born. Yet this wasn’t an easy childhood, the F50 certainly had it’s detractors st the time who compared it with the F40 and the McLaren F1 – both much more race oriented. But time has shown the influence of the car as a modern supercar, and how irrelevant a direct link with competition has become. It was the easy-to-drive supercar that was moth-balled by most owners as an investment!

FYI the cost of the 959 was extraordinary, even for a company has a slightly mad streak when it came to competition cars – remember the eventually incredible 917 almost sent the company to the wall. The 959 sold for US$225,000 – you could buy a Countach AND a Testarossa for that! Not only was that expensive, it’s estimated it actually cost the factory around US$530,000 to build each car! German madness!

However the Porsche legacy showed that by building technology into a high-performance car you could make it far easier to drive – and therefore inherently safer. This meant that driver skill was no longer a requirement for ownership – a key marketing strategy of a supercar.

It also highlights the incredible ‘bang-for-buck’ of motorcycles and especially the GPz900r.

It could out-accelerate both the Porsche & the Ferrari but cost just US$4,399 – that’s less than ONE PERCENT of the actual cost of the Porsche. Interestingly this superbike vs supercar purchase price comparison is very similar today.

- 1984: GPz900r to Lamborghini Countach = 2%

- 2020: BMW s1000rr HP4 to Bugatti Veyron = 2.3%

The modern Superbike

So, are modern superbikes as pretentious as supercars?

We showed that a 2020 superbike is only about 2% of the cost of a supercar – the same as what it was in 1984. The sobering reality is the infaltion corrected affordability of modern machinery. The corrected cost of the GPz900r (2.53x) is just 13% of the purchase price of a 2020 BMW ss1000rr HP4 and still only 47% the cost of a Ninja Z H2, a more ordinary motorcycle.

I mean crikey, doesn’t the Ninja uses a same steel-tube frame & engine as stressed member design as the old GPZ900r?

The numbers show three things.

- The incredible value of motorcycles of that era. Remember the GPz900r was the fastest motorcycle you could buy in 1984, yet amazingly it was not the most expensive motorcycle of the time. As was the case with the CB750 this highlights the absolute brilliance & significance of the designs despite still being built to a budget.

- The Law of Diminishing Returns, the reason why competition is expensive. Making machinery faster simply becomes more & more expensive for smaller and smaller performance gains.

- That modern superbike & supercar is as much a luxury product as it is performance;

Luxury: something adding to pleasure or comfort but not absolutely necessary

These shows how the developing market of supercars & superbikes has magniied the price of the machinery – you are now paying significantly more for the same contemporary performance.

But don’t be offended nor take this opinion personally if you own one of these amazing motorcycles.

I totally acknowledge that a 600 (especially a 636!) is more than enough motorcycle for road use, yet I ride an old 900. Interestingly in 1985 Kawasaki released the GPz750R (900 with smaller engine) and the new perimeter framed GPZ600R. Around a racetrack the 600 more than held it’s own. When it comes to handling precision you simply cannot beat physics – the 600 is 30kg lighter, wheelbase is 65mm shorter (1430mm) with 15mm less trail (97mm) than the 900 (& 750) geometry. This itself gives an inkling as the design for the 900. Back then 150mph was as good as it got and as motorcycle speeds increased so does the need for safety, and it becomes impossible to optimise engineering to cover the ever-widening operating range. This isn’t a modern question, this quote is from 1984:

“The Ninja says motorcycling is on the way to 150mph street bikes: they will be the fastest road-going production vehicles in America. One-fifty bikes will lose versatility because they must be engineered up to these speeds even though the bike will be ridden, maybe for the most part, down at legal limits.”

The poignant phrase here is legal limits. So just like supercars, superbikes are rarely going to be ridden in anger, on the road or the track.

Again the true marketing power of a superbike is simply ownership desirability over it’s competitors (or lower specified models). If a GPz900R rolled up to anything else on the road in 1984 it could probably beat it. That’s pretty amazing. And because of the phenomenal publicity generated by the bike (and Top Gun) nearly everyone else knew it as well – especially other motorcycle riders. They also knew that you didn’t even need to be an advanced rider – so superiority by ownership became a reality.

And perhaps this is what distinguishes the GPz900R from it’s esteemed predecessor, the CB750. The Honda was a Titan of motorcycles, the GPz900R was the Titan of almost everything on the road – without having to do anything.

The GPz900R was one of the first motorcycles that gave the average rider access to that ‘aura of invincibility’ – something rarely seen in the motoring industry even today. Yet surely one of the core aims of a modern superbike.

The marketing genius of the modern superbike (& supercar) is that it focuses on the emotions of the rider AND the emotions the motorcycle will give to an external observer – even before it has turned a wheel in anger.

Of course desirability is a deciding factor for all vehicles – it’s just that supercars & superbikes take this emotion to an extreme level with the goal of having the purchaser to throw logic completely out of the window. They want the desire to own it to completely out-weighs what it costs, it’s actual technical performance, or how the owner intends to even use it. It’s simply brilliant.

Another interesting development of modern bikes is that although new technology is there to allow advanced riders to optimise the bikes performance, it also allows mere mortals to ride (or as in 1984; think they can!) these incredibly powerful machines in relative safety. Again brilliant – although perhaps the complexity of considering lower-skilled riders is one of the reasons for the increased relative cost.

The fun YouTube video below compares the 2005 Suzuki GSX-R with a 2020 Panigale, with both data & opinions/conclusions that match my thoughts on modern superbikes. It also confirms that pure track performance is no longer the highest design priority for a modern superbike.

But of course I’m totally one-eyed & biased so here’s an alternative assessment of the superbike!

1983. GPz750 Turbo

Without the GPz900R this bike would deservedly have received much more recognition. As it stands it’s still a cult classic!

Although the turbo era can be seen as purely a marketing event, Kawasaki engineers had been working on the engineering since 1977 and had test bikes in 1980/1. Link to 750 turbo prototype. The Kawasaki was the last but best of the blown bunch, with the greatest capacity and the turbo location carefully determined to minimise lag.

It was fuel injected (YES – but 900 still used carbs!), well thought out and engineered, looked great and handled better than either the 1100 or the standard 750 (it had a different frame). This was clearly a period when Kawasaki engineers were right at the top of their game.

But it was simply out-classed at everything when the Ninja arrived, including acceleration (an often quoted myth is that the turbo was faster).

Perhaps the best summary of the bike came from Kawasaki themselves, because this observation was made at the extremely expensive two-day press introduction t the Turbo at the Salzburgring, Austria, by journalist Mark Homchick in April 1983.

Kawasaki’s Hank Hosoi offered this remark, somewhat cryptically: “The Turbo is only a step to the future, so we are trying to keep the cost down”. Maybe that means Kawasaki is already spending heavily on a whole new generation of engines.

So Mark your instincts were spot on, with the GPz900R revealed at the Paris Motor Show just 6 months later.

1984. The competition

The 80’s were indisputably the era of japanese motorcycling dominance.

It’s worth noting that at that time all japanese manufacturers were building or planning modern bikes, they all realised the era of the brilliant Honda CB750 was passing by. Kawasaki themselves aptly demonstrated this transition period by also releasing the GPz750 Turbo the best of the blown bikes. It wlso released in 1984 with similar raw performance figures and looking remarkably similar to the Ninja – yet they were totally different bikes. The old & the new.

Designed as a superbike, the air-cooled Yamaha FJ1100 was a wonderful bike and a worthy street competitor to the Kawasaki – and it is a bike deservedly considered the first genuine sports-tourer.

Suzuki were still working with the spectacular the Katana range, and (thank goodness) released the GSX 1100S Katana. Yes these bikes were old-school but what a glorious way to finish up – these are genuine motorcycling design classics.

But even with these massive engines (~20% bigger) and the Katana’s clearly sporting design, these two air-cooled bikes simply could not match the GPz900r – in the straights or in the bends.

Yamaha also released the two-stroke RD500LC – the street version of Kenny Roberts MotoGP championship bike. The little Yamaha liquid-cooled (LC) two-strokes were legendary for their power, the RD350LC was almost unbeatable in it’s production racing classes. Releasing a bike based on the brutal, fire-breathing monsters that were GP bikes promised a spectacular & desirable road machine. Unfortunately despite great fanfare and absolutely ‘looking’ the business this motorcycle was a mere shadow of the MotoGP bike. “As two strokes go the big RD is a pussycat”. Ouch.

The Honda VF1000r had similar potential, growing in engine size from the championship dominating VF750f. This completely competition-oriented variant of the VF1000f road bike it came with adjustable clip-on handlebars, single-seat cowlings, even gear driven cams – wow! It was powerful & a racing motorcycle released as a road bike simply so it could be homologated & raced. It was also one of the very first bikes to run radial tyres, apparently developed in-house by Honda. That alone tells you the extent of their R&D budget……

It was by all definitions a modern superbike and it looks exactly like one too. The problem was it was a bit of a dissapointment disappointment.

The gear driven cams are very cool, but the bike never achieved the talked about 260km/h top speed, it was super expensive, beaten on the road & the track by other bikes. Sales were disappointing and the damage to the Honda competition brand (compounding long-term perceived camshaft issues with the family of engines) was so bad they pulled the plug on the entire V-series of motorcycles. Ouch. The legendary Wayne Garder rode it in Australian Production bike races and described it as ‘riding a marshmallow‘. OUCH!

The brilliance of the GPz was that it was designed as a total package. Of course this has been done before, the difference was this was a motorcycle designed to be close to the best at everything. It was a game changer – and Kawasaki did it with a 900.

At a time where most manufacturers equated performance with engine capacity – the GPz beat them all.

Bike Magazine article road testing five performance bikes from 1984.

The little Ninja was king of the road, and it’s clear superiority against bigger-engined competitors made it clear to other manufacturers that they were going to need serious R&D if they wanted to de-throne it.

The Ninja made every other performance manufacturer rethink their definition of a performance bike. And they certainly did.

Suzuki developed the legendary GSX-R bikes, Yamaha created icons like the V-Max, and with the 851 Ducati began the resurgence of this famous Italian brand. Honda went back to the drawing board and 1988 released the VFR750R RC30 for superbike racing, then in 1992 the CBR900RR Fireblade – a light & responsive motorcycle designed around a water-cooled, inline-4, 900cc capacity engine.

Sound familiar? LOL.

1984. Isle of Man Production TT

In May 1984 the Production TT was re-introduced at the iconic Isle of Man, a ‘racetrack’ best descibed by the legend Valentino Rossi as:

The GPz900r, released just 4 months earlier, finished first (Geoff Johnson on #2), second and third!

OK, third was penalised back to fifth (grin) but this is still demonstrates the wonderful high-speed package and confidence-inspiring ride that was the GPz900r – basically straight off the showroom floor. And this was a category where the maximum engine size allowable was a whopping 1500cc! The bike competed well over the next few years in Production racing around the globe, in Australia racing toe-to-toe against the Hondas (VF750r & VF1000f) and the Yamaha RZ500.

It didn’t always win (especially on tight tracks against lighter more nimble opponents) but what makes the story of the design even more impressive is that all of these were designed specifically for competiton.

The GPZ900r wasn’t – it was a street bike that was so good it could still match it with these bikes on the track.

It is this track competitiveness that suggests the common categorisation of GPz900r should be reconsidered. Because if the fastest production motorcycle in the world is also one of the best production racing motorcycles of it’s time…..then surely it’s more than just a sportsbike?

1984 to 1986. Mt Panorama, Bathurst Australia

In 1938 the very first race on this famous Australian street circuit was for motorcycles, but like the Isle of Man it is a challenging racetrack for fast motorcycle racing and now, understandably, is considered too dangerous. But throughout the 70’s & 80’s the Easter races were legendary (controversial as well) for riders & spectators and incredibly well supported by manufacturers from all over the globe.

For example Bathurst was the first ever victory for the Ducati 900SS. Well not quite! In fact for the 1975 race the official Ducati importer created the 860S, a 750S with high performance parts specifically developed to tbeat the conquering Z1. And it won, but of course the questions as to how this was a ‘production bike’ soon came up and the importer was soon advertising street versions of the 860S. But of course it never eventuated, the production bike was the 900s!

But surely one of the great superbike race stories was the 1983 Arai 500 at Bathurst.

- During the 80’s the annual race for unlimited superbikes (up to 1200cc?) was the Arai 500, 499.93km or 81 laps! This long, hard and fearsome race created great comradery amongst teams & riders and even manufacturers, best demonstrated in 1983. Brought out just for Bathurst were two brand new Honda Formula One prototype bikes (VFR860) each worth AU$60K, that’s over AU$207,000 in 2020. But at full revs there was a major concern they would not last the distance, so the factory riders used the older ‘tried and true’ VFR1000’s. In the sheds next door was the Suzuki team, because one of their riders was unavailable they had decided not to enter their bikes leaving the other rider, Robbie Phillis, without a ride. with an unused bike sitting next door the obvious question was asked, and with the blessing of both factories a deal was struck at 6pm the night before the race, and Robbie (and the Suzuki team) were given one of the brand spanking new Formula One Hondas to compete.

The relevance of Mt Panorama (and the Isle of Man) is that these aren’t short, twisty circuit GP-bike sprint races – this were fast (280km/h down Conrod Straight) and long endurance events. There is almost no margin for error – if you come off the track you crash. This was the type of competition that manufacturers would consider when developing superbikes (yes that’s what they were called back then) like the GPz900r. And it makes complete sense – these were street circuits and surely these were the sharpest & longest torture-tests that you could give any production bike (and it’s rider).

If you won here you had every right to be called a superbike.

The GPz900r also heralded in the moment when the production motorcycle frame, chassis and handling were all so good straight from the factory that custom race-builds were no longer a competitive advantage.

In 1984 Rob Phillis won again on the new GPz900r, and the bike won again the following year in 1985. And because these were Easter events (March) this means the first significant race win for the GPz900r was in Australia (Isle of Man held in May/June).

Of course the only video I have found is 1986 when the GPz900r didn’t actually win Bathurst!

But from 1984 to 86 (in 1987 capacity was capped at 750cc) the Ninja was super-competitive in this competition winning plenty of races. Earlier this year you could even have bought one of Len Willing’s bikes, and in 1986 he came mighty close to winning, out-braking himself with a desperate lunge on the very last corner!

A great circuit and this was a cracking race, and one which gives us some great footage of the old girl being ridden in anger on the racetrack.

1986. Top Gun: 'I feel the need - the need for speed'

Yep – corny as.

But despite several cringe-worthy moments (even for the 80’s) ‘Top Gun’ was a world-wide commercial success – grossing over $356 million. The marketing & consumer exposure for Kawasaki was immeasurable – successfully associating a $20 million fighter jet with a $4,399 motorcycle is pure marketing gold.

Yet an the un-badged version is used in the movie.

It is still incredible that Kawasaki were not directly involved with Paramount Studios. Yes, they knew that the GPz was the performance motorcycle of it’s time – but it is still surprising that it seems like they simply couldn’t care less whether it was in the movie or not. The 1982 movie ‘ET’ grossed $792 million – the product placements in that film were surely worth every penny many times over.

Remember we are only talking about a wholesale cost of just $2,800…..

2020 Update: Curiously there isn’t a lot of definitive information available. Perhaps understandable, as both Japanese manufacturers and movie studios were pretty secretive industries. So everything is second or third-hand of non-verified forums & chat rooms.

It seems most probable that Kawasaki were going to provide the bikes, but the licensing negotiations and paperwork were so onerous that Paramount just gave up and bought them. So de-badging *might* have been a legal requirement but also one I’m pretty sure they were quite happy with.

The most relevant fact is that despite the bike only being on the market for a year there was only one motorcycle they could ever use in the film, there really was only one performance motorcycle jet fighter pilots would own if they had a ‘need for speed’. I have also read the Kawasaki was used at the insistence of Cruise himself (un-confirmed) .

And there is no question the bike plays it’s role perfectly in the film.

For those who weren’t around when the Ninja was released (nor Lou Reed fans), this is perhaps the best example of the hype generated by the GPz900R. Because even before the movie was released it was universally regarded as the best performance motorcycle of the time, so it was the only genuine candidate for the role.

And as I always remind folks, you need to put this into context. In 2020 there is at least half a dozen (maybe more) hyperbikes that you could argue are right for this role. In 1985 there was one motorcycle that stood head & shoulders above the rest, the mighty GPz900R.

Interesting trivia, director Tony Scott had previously produced a commercial racing a SAAB 900 Turbo with the SAAB Viggen, a scene clearly replicated in the movie.

Note: there is an urban myth that the bike is a GPz750R

Firstly is it possible? Yes, but highly unlikely.

I think this myth comes from Tom Cruise, like many actors, being small in stature – only 5′ 7″. Well, I’m 5’7″ and ride my A8 fine. You tend to sit *in* bikes from this era rather than *up & on* as is the norm for modern performance bikes. Not only that, but ONLY the cylinder bore & stroke is changed for the GPz750R, everything else is exactly the same, including seat height!

The GPz750R was simply lazy work by Kawasaki, most likely created so they had a bike they could run in the 750cc World Superbike series. Not a bad motorcycle, but with the enormous shadow cast by the universally applauded 900, the little brother was too big, too heavy & and under-powered. Hardly a good combination for a performance bike and clearly not the choice of a jet fighter pilot….

IMHO this www.imcdb.org article shuts the door on that one.

1985. GSX-R750

Some folks consider this the first modern superbike, and I know enough about motorcycle passion to not argue this with them directly! Aluminum perimeter frame, flat-side carbs, high tech (air/oil cooled) and race-bred for the 750cc Superbike series. An amazing, potent little beast of a motorcycle.

But was it really any different to the incredibly successful 1983 Honda VF750f?

Because despite the adoration of her owners (which I totally get!) it was still slower than the GPZ900r in both top speed and 1/4 mile acceleration. Not by much and impressively done with less cubes, but it simply wasn’t the fastest bike on the planet. I actually think a very rose-coloured reviewer accidently sums it up best.

The early model was a lively beast that took some taming even though it was light years better than any road machine previously seen.

Well riding ‘a lively beast that took some taming’ at 150mph clearly shows wasn’t light years ahead of the GPz, with the Ninja universally acclaimed as having impeccable handling at high speeds. On long country rides the GPz might not only get to the destination in front of the Gixxer but with a lot more ease & comfort for the rider. Yet this is seen as a strength not a weakness.

So why have superbikes become so edgy?

The GPz900r was the bike that allowed street riders become speed demons, the effect of this bike was as dramatic as a new sword slashing through the undergrowth. But ironically her capacity to do this with such aplomb was probably also her Achilles Heel. Once riders (and reviewers) got over the surprise (shock more likely) that your average rider could pilot a production bike at these speeds, everyone soon realised that this new blade had plenty of scope for sharpening.

Did the Gixxer sharpen or even reform the blade?

Maybe, but it simply doesn’t matter because the blade was already made.

it was simply reforming and sharpening the blade that had already been created with the Ninja. A blade which has then been tempered and sharpened again with the 916, the Fireblade, the GSXR-1000 and every modern superbike that has followed.

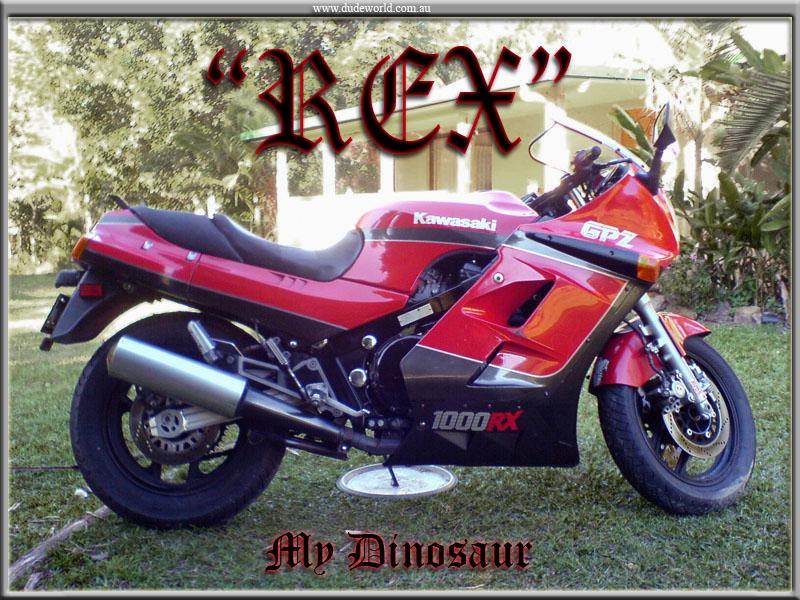

1986. GPZ1000RX

The GPZ1000RX (Ninja 10000R) was technically the successor to the GPz900r, but I think Liam from dudeworld reads between the lines well.

The story of this motorcycle is almost as fascinating as the GPz900r – but for the wrong reasons. With a 1000cc engine developed directly from the GPz900r (58mm stroke vs 55) this gave Kawasaki the fastest bike of 1986 – but that was about it. It’s ponderous chassis (based on the GPZ600RX) couldn’t manage the power or the weight (an overweight dinosaur) and reviewers universally preferred the old Ninja.

Note: some harsh purists even make the observation that that it is an unrelated bike because the prefix is GPZ (uppercase) rather than GPz! However I have read that the capital Z was also used by Kawasaki in 1991 to distinguish the ‘new’ GPZ900r from the original GPz900r!

It simply astounds me that Kawaskai spent 6 years (SIX!) developing the GPz900r, a motorcycle released to universal acclaim that reminded everyone how you should build a performance bike, yet just two years later they revert back to the ‘old school’ mentality of simply shoe-horning big engines into frames.

Why?

As Liam from dudeworld suggests it looks like a bit of a scrambling by Kawasaki. Most of the bikes of this era l had square-section perimiter frames, so it’s not hard to see marketing as deciding the tube-steel backbone frame design of the GPz900r wasn’t considered modern enough. This does have all the overtones of corporate decisions, because it seems probable that any engineer who had worked on the GPz900r would realise the handling of the GPZ1000RX wasn’t going to compare with a GSX-R let alone the Ninja.

Ironically tube steel frames have shown their enduring value to a frame design used on subsequent motorcycles like the Ducati 916 and even the modern Kawasaki H2.

So whilst I do think Kawasaki missed an opportunity to develop the GPz900r further, I think this is simply a window into the remarkable world that was motorcycle development in the 1980’s. Honda (VFR1000r) and Yamaha (RZ500) tried to release racetrack-bred bikes for the street and failed. The Kawasaki was an excellent endurance race machine (results proved it) and all logic says these competitive demands are far more related to street use.

But then Suzuki got the GSX-R750 package spot on, with a design that took the street performance bike (and modern superbike) down a different, edgier path than the GPz900r. I doubt Kawasaki knew where to look next.

The superbike legacy of the GPz900r

“If you rode the Vincent Black Shadow at top speed for any length of time, you would almost certainly die.”

After decades of exceptional superbikes it seems obvious that fast motorcycles need to handle well, but that simply wasn’t the case until the arrival of the GPz900r. At that time European (and most 750’s) bikes handled well, but were easily out-gunned by the faster Japanese big-bore bikes. But as the power went up handling, ridability & safety went down.

The GPz900r design is famously described as having the handling of a 750 & the power of a 1000. Despite still being a heavy motorcycle the bike impressed every single reviewer with it’s stabilty, precision and agility.

It’s design showed a great understanding of what is required for a progressive performance motorcycle – even today. Learn from the past, use & optimise what you already have, and push the boundaries for what you want tomorrow.

Yes the anti-dive forks were rudimentary by modern standards (and not liked by all), but development of this technology shows great insight by the engineers as to where motorcycles needed to improve. Power/weight/size all pointed to a small capacity engine making aerodynamics, still an emerging technology in 1984, critical to optimise top end performance. Although not the first full fairing motorcycle (1980 BMW Futura) with a Cd of just 0.33 the GPz900r it was incredibly effective yet still looked futuristic & stylish to the public. To put this into perspective, the 1992 Ducati 916 has a Cd of 0.38.

In 1984 it was, quite simply, the ultimate performance bike. But more importantly : it was ridable.

The GPz900r was the first ‘fastest in the world’ motorcyle that behaved so well it gave even the average rider the confidence to pilot the motorcycle – fast. This would have surely significantly increased the number of owners (not just the crazy ones) who then considered owning a performance bike.

And everyone else soon realised that it ano longer mattered who was in the saddle – the GPz900r would probably win. With it’s striking looks and public profile it was surely one of the first motorcycles to portray an ‘aura of invincibility’ that meant when you were sitting next to it at the lights, you were beaten before you even started.

And riders got that simply by owning it.

It also showed company accountants that if you can achieve these lofty engineering goals then the buyers would line up for high-end performance bikes (with potentially high-end price-tags) so there were measurable direct and in-direct benefits to company profits.

Performance, desirability, ridability. A motorcycle that opened the door for many new owners and was an economic success for the company. The Gpz900r meets all of the criteria of a modern superbike long before the market even existed.

And it was a snowball that started an avalanche. In many ways a victim of it’s own success, the motorcycle development that followed the GPz900r was extraordinary. Economics mean manufacturers need a production-run of several years to pay for their investment (and at six years the GPz900r was significant!), but this was an extraordinary period where if you weren’t continually improving you really were going backwards.

The 1986 (to 89) replacement for the GPZ900r was the larger-capacity GPz1000RX/ZX1000-A. Faster in a straight-line it lacked the overall poise of the original design and was simply surpassed by new releases from other manufacturers.

It’s reign at the top was surprisingly short, as the GPz900r was quickly surpassed as the best performance motorcycle.

But despite this the Ninja had an extraordinary production run, out-lasting it’s 1986 replacement (GPZ1000RX) and even it’s successor, the ZX-10! Returned to production because of buyer demand sales eventually stopped in the US in 1993 & in Europe in 1996, but local japanese demand for this iconic motorcycle, especially as a sportsbike, was so strong that production continued right through until 2003. Some observers suggest the ONLY reason you can’t buy one today is tighter emission laws.

Long production runs are an incredible achievement for any type of motorcycle, but absolutely unprecedented of for what was designed as a cutting-edge performance motorcycle AND for a design that remained virtually unchanged throughout it’s entire production lifetime.

It really is no surprise that Ninja has become one of the most successful and recognisable motorcycle brands – ever.

1994. Ducati 916 - the first modern superbike

There have been plenty of wonderful & iconic superbikes released since 1984, IMHO the most influential on modern superbike design is the beautiful Ducati 916. I love my GPz900r – but I’ll happily admit this is a piece of motorcycling art. I’ve already mentioned it’s origins were the 1987 Ducati 851 – using the same magnificent V-twin and fuel injection. An honourable bike itself, but it does look…welll…japanese!

There is a core mantra of product design: form follows function. This means the look of the product should be related to what it does – in one way or another. However it doesn’t mean that an industrial product can’t look interesting, consider the Alessi fruit juicer. And visual appeal has always been a core part of marketing & generating publicity.

Form follows function also applies to motorsport. The racer cares only for absolute performance – the smallest advantage is desirable when lap times are measured in fractions of seconds. Yes their bike might look terrible – but ultimately only winning counts. Interestingly due to fluid dynamics speed often produces flowing.striking forms – just think of marine predators, birds of prey or fighter aircraft.

But that is not always true with machinery, best exampled by the 1999 Suzuki Hayabusa GSX1300R. Obviously at +300km/h aerodynamics is critical, and although brutal, purposeful, intimidating and incredibly fast – it’s a stretch to say that the mighty Busa looks good.

The Ducati 916 was also at it’s core a race design, but the incredibly talented Tamburini also deliberately designed it to look good. It’s not to say that other bikes didn’t consider visual appeal as important, but no other motorcycle (IMHO) has combined the two criteria as well. The best example of this is the rear swing arm. Like Tamburini himself I’m not toally convinced with the engineering logic, but one simply cannot argue with the impact it has visually.

An interesting similarity is both use a steel tubular frame – despite the GPz900r’s design being considered as ‘old school’ by many of the aluminium and/or rectanglar section framed bikes that superceded the Ninja.

And the legacy of this motorcycle is that Ducati now had a design that completely distinguished the Italian brand from other manufacturers and had buyers queing up to own one – no matter the price tag. It’s not rocket science that Ducati (and other manufacturers) soon realised that this could be a very profitable market.

So serendipitous design or not – the brilliance of this motorcycle is that it does everything – beautifully.

It had some technological advancements (FI) and it was an incredible success on the racetrack but it probably didn’t need either of these – it would have been a classic motorcycle no matter what. It tweaked the modern superbike template to include criteria much harder to define (and design): hype, aura and owner desirability.

Arguably the same criteria the GPz900r created when released a decade earlier.

2020. Yamaha YZF-R1 - rider assist technology

Even ignoring the basic physical unsuitability of a superbike for road use, as here’s a quick thought as to why modern superbike technology is not as competition oriented as we might think – the incredible rider-assist features of the Yamaha.

Apparently based on the 2012 MotoGP bike system, where every corner of every circuit is configured to suit the specific rider and the track conditions at the time. Fancy stuff and exactly the no-stone-unturned competition bias expected at this level. But this option isn’t available to mere mortals on road bike – instead you get a system that lets you set the different rider assist options as a saved group of settings. Now this makes complete sense because you don’t know what the corners, surface conditions, or atmospheric conditions are.

But that’s road riding – but at a race track you do know these.

Yes you can tweak the assist-options, even save different sets – like wet weather. But you can’t customise to the actual track design itself. Nor can you change these settings safely mid-race nor even mid-ride (which makes sense), however again it’s application for competition is limited.

I’m not saying this technology isn’t beneficial at the track, I’m not saying they don’t improve performance at the track – and I totally agree this is technology derived from competition.

But consider a competition superbike – narrow peaky engine power, deliberately un-stable chassis design (short wheelbase & steering rake) features desirable for a racetrack that make it unsuitable & arguably dangerous for street use at modern speeds. Most reviewers always comment as to how this technology really helps the novice rider. But is this skill of rider really the person to be racing a litre superbike in anger around a racetrack?

So the question is are they on the road superbike for competition advantage or simply required for rider safety?

So are superbikes all hype?

Well hype is Marketing 101.

And this is a tricky one, because it makes economic sense for manufacturers. Superbikes allow a range of bikes to be based on the same platform – a sensible economic model. And more importantly they can be premium-valued at what a buyer will pay for them – not what they actually cost to manufacture.

But are they really that good?

You can’t compare an older motorcycle with modern machinery – you measure by what it replaces. The fact is that modern motorcycles simply aren’t the significant jump in raw performance from decades older machinery and on the road the performance difference between superbikes and supercars, brought together by the GPz900r, is now getting wider & wider.

Here are the acceleration figures (reviewers not manufacturers) of the three bikes I would love in my garage, and just for fun a modern superbike:

| Year | Motorcycle | Top Speed (mph) | 0-60mph | 1/4 Mile | Source |

| 1976 | CB750A | 97 | 10.0 | 15.9 | Source |

| 1984 | GPz900r | 151 | 2.9 | 11.09 | Source |

| 2005 | GSX-R 1000 | 183 | 3.1 | 10.2 | Source |

| 2019 | Pangiale V4r | 181 | 3.22 | 11.15 | Source |

Yes there’s much more to a motorcycle than numbers, and acceleration times are more affected more by rider, conditions, gearing, blah,blah. But what these numbers highlight is two things.

- the GPz900r was a significant jump in performance from the previous significant performance motorcycle

- it set some performance standards that are still relevant today against modern machinery

Some consider the track times of a 2005 Suzuki GSX-R1000 to be better than many modern superbikes, and the reality is a modern 600 has more than sufficient power & speed for both track and road use. There is no question that modern bikes have a broader range of power, rev much higher and are easier to ride, but any large capacity performance motorcycles for road use is totally unnecessary!

Ultimately modern superbikes (and supercars) are technologically better but for each new generation the performance gains are simply getting smaller & smaller. So they are here because they suit modern marketing product turnover and obviously because owners want them. And that’s perfectly OK!

But they simply do not have the impact on the motorcycling industry that defined many motorcycles that preceded them – and perhaps they never will.

With only minor changes, the GPz900r was in production for an incredible 19 years. This longevity is impressive for any motorcycle and incredible for a performance motorcycle.

The 1969 CB750 was analogous to the the creation of steel – immediately relegating everything that was iron into history. Kawasaki engineers then methodically and carefully crafted this steel into a blade (Ninjato) that sliced through the motorcycling world; the1984 GPz900r.

This blade was the modern superbike, which was then sharpened and even reformed by many wonderful bikes that followed.

Agree to disagree - or not!

2034 Celebrations

A forum to discuss ideas and help manage special events planned to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the GPz900r.

GPz900r Bikes

An online database of bikes from around the world. Registration is totally free and can be completely anonymous.

About the Site

My family loves older vehicles, the newest one we own is 2003! But I am acutely aware of the ownership complexities especially:

- they often need more 'hands-on' mechanical work &;

- there often isn't any local expertise from the service centres;

- there is often no new parts available from the manufacturer;

- parts often have to be sourced 2nd-hand or from overseas.

So we often end up doing a lot of the research & work ourselves and this information gets stored either locally with the bike or online forums - although finding the useful parts in these forums isn't always simple.

The original goal of the site was simply somewhere for me to record service work & contacts on my GPz900r so that my kids (the one that likes bikes anyway!) could easily access it - it doesn't concern me if it was publicly available.

I then realised that with this online structure in place I could also offer it to other owners, and the site could potentially expand to record other owners experiences and expertise , meaning we can learn from others but also pass on this knowledge to subsequent owners of these wonderful motorcycles.

At least Covid-19 has given me plenty of spare time to pursue my passion for the motorcycle!

Location

Adelaide

South Australia

gpz900r@motoshoot.com.au

Timeline

1983 - Honda XR200

1984 - wanted a GPz

1985-2013 - cars+family

2014 - finally got one!

Disclaimer

The information provided on this site (or links) is personal experiences from non-professional home-mechanics, so neither it's accuracy nor it's validity can be confirmed. If you need professional advise please visit your local Kawasaki dealership or a qualified industry professional.

Like riding any motorcycle, at the end of the day the only opinion that really counts is your own!

.ashx?h=493&w=740&la=en&hash=1A1A96829B2BD25392599B210E4754768D75C4AC)